How We Meet

We first meet on a boat, a chartered schooner afloat beneath a sea of endless stars. On a zero-G rocket, floating weightless in the atmosphere, Earth twirling blue-green below. Swaying on a sweaty subway pole on the MTA in a zenith summer. Seated on the backs of Saharan camels, marching steadily toward the oasis—or mirage—that will save our lives—or fell them.

We first meet on a boat, a chartered schooner afloat beneath a sea of endless stars. On a zero-G rocket, floating weightless in the atmosphere, Earth twirling blue-green below. Swaying on a sweaty subway pole on the MTA in a zenith summer. Seated on the backs of Saharan camels, marching steadily toward the oasis—or mirage—that will save our lives—or fell them.

Each time we meet for the first time, the therapy algorithm finesses the experience. It replaces the previous session, the shared memory that used to be. We only know where we’ve been because our patient notes are open; I can’t actually remember how it felt, the flesh and bone and raging hormones of our real first encounter. It’s buried deep in our subconsciouses now, so deep we’ll never recall it. Which is where our problems are supposed to go, too, once this brave new treatment starts working. TMR-T, the Therapeutic Memory Recodification Technique. The brainwaves of the future.

Hilarious, I find, that the TMR-T trial is covering the cost of our fertility treatments in full, while our insurance wouldn’t even cover semen analysis or injectables or egg retrieval. All it costs is the right to poke around in our heads twice a week. You don’t find this hilarious at all.

+-

“Croissant?” Philip asks Nora, who shakes her head.

He shrugs and pulls a pain au chocolat from a bakery bag. Takes a bite. Doesn’t care that he’s getting pastry flakes all over Doctor Crain’s office chair.

She’s too nauseous to eat. Hands in her lap, wringing an imaginary rag. They’ve been in this office—in these chairs—so many times now that she could recite his desktop paraphernalia from memory. A blown-glass sperm, violently green, zipping toward an egg. A plush pink uterus, smiling, its ovaries little hands. A flesh-colored rubber embryo, alien-looking, a pinto bean with eyes and a tail.

“Sorry for the wait.” Doctor Crain at the door. His usual opening line.

He sweeps in, white coat flailing, and Nora thinks of the White Rabbit. I’m late. Late is something she’s never been, a sensation she wants so much it burns.

Please, she thinks, oh please oh please oh please.

The doctor sits down across from them and folds his hands. This is how he starts bad news. Nora feels her muscles seize, the tightness in her throat. She’s not going to cry again. Not here. To Nora’s right, Philip takes another bite.

“So,” the doctor begins, “as you know, we got twelve eggs in our last retrieval, eight of which didn’t take to the insemination. That left us with four embryos, one of which stopped maturing, so three that we ultimately biopsied and sent to embryology for sequencing. Unfortunately, two came back with severe abnormalities—beyond the realm of what would reasonably make it to gestation—and the last little guy, though not as severe as the others, has several genetic predispositions that make it unethical for us to proceed with the transfer.”

Nora blinks and swallows, swallows and blinks.

“I’m very sorry,” he adds. “I know it’s not the news you wanted.”

“What do you mean, genetic predispositions?” Philip is asking.

As Doctor Crain reviews the sequencing report, the two men hunched over the desk like engineers at work on an equation, heirloom pen and half-eaten croissant in their respective hands, Nora stops listening.

“So, what now?” she finally interrupts them. Louder than she intended but pleased at the effect. They stare up at her like they’d forgotten she was there. “What do we try next? What are our options?”

Doctor Crain removes his eyeglasses and wipes them with a microfiber cloth patterned in dancing squiggles of sperm.

“You should have a bleed in the next week, and then we’ll try again. Another retrieval round.”

“With the same medications?”

Doctor Crain nods. Nora frowns.

“We’ve done this twice now, with those same medications. Why will this time be any different?”

Doctor Crain sighs. It reminds Nora of her father.

“We’ll modulate the dosages. Have you in for more frequent monitoring. And from the reports I’m getting from the clinic, the TMR-T is beginning to help with your stress levels. That’s key now. As you know, we can’t reprogram your hypothalamus, but if we regulate your emotions, it may help counteract your pituitary dysfunction, giving us a much greater chance at success.”

“I guess I still don’t see what memory has to do with my emotions. How is changing our first date going to get us a baby?”

Doctor Crain frowns, pinches the bridge of his nose.

“We’ve been through this already, Nora. The trial’s experimental. But it’s been remarkably effective in cases like yours, where neurological-reproductive malfunction presents without a physical pathology. It’s all stress-related. Emotional. And I am not going to exacerbate it by feeding into your Type-A neuroses. Calm and steady. We’ll get there. Now, Philip, you were asking about the chromosomal mapping. Let me take you through the lab report.”

+-

If I close my eyes and try to remember it now, the first time we met was in Paris. It goes like this.

We’re backpackers in a rundown digitel in an arrondissement in the low teens. Nineteen, maybe twenty years old. Live as wires. We stay up all night talking and making out beneath the blinking strip of charging stations in the scant lobby, drawn like moths. When we finally venture out, adrenaline drunk at four in the morning, so late it’s early, wanting so badly it’s an almost physical pain, the sunlight weeps down the Champs-Élysées, bleeds across the wet pavement like liquid gold, and in this memory—the tell-tale sign of its manufacture, the dead

giveaway—the camera pulls back as we kiss beneath an antique streetlamp. It’s like watching a dream, something out of a Jacques Demy flick. Too beautiful to be real.

In this treatment, we speak fluent French, a language neither of us have ever held in our mouths, and you have paint beneath your fingernails, orange and blue, instead of clean, accountant’s hands. We are different people in this memory, so different it’s hard to draw a map to now.

When I bring this up during our post-TMR-T debrief session, the only part of the program where you and I are separated, alone and honest with our thoughts, the algorithm—or, at least, its android,

Altheia—smiles and reassures me that it’s what we need to fix who we’ve become: a distance wide enough to keep us from looking back. Here, we go only forward.

+-

“Oh, hey, hey. Don’t do that. Nora? Come on, Honey. Don’t cry.”

Philip finds her in the bathroom. She’s red and blotchy and there are pregnancy tests on the floor, three of them, side by side on the tile beside her balled up pants. It’s only been a couple days since the transfer, and Doctor Crain told them not to test at home, to wait the full week before the in-office blood work, but Philip won’t dare remind her of that now. Instead, he takes her in his arms and waits.

“Lip, what if it never happens?” She’s whispering, but in his ears it screams.

He hates seeing her like this, the joy siphoned away. It’s ruining their lives.

“Then it never happens.” He is numb to this conversation, to all the hundreds of times they’ve had it.

“But what’ll we do? What else is there?”

Philip hesitates. He could say what he always does. He could tell her not to worry, that it’s only a matter of time, that they have to stay positive.

Or he could be honest. Just this once.

“I mean…there’s us, Nora. Just us. Like always. We could sell the apartment. Buy a boat and sail around the world like we always talked about, and have sex without taking our fucking temperatures first. Live great lives and die when it’s time and leave our bodies to science for the next suckers trying to procreate.”

“Be serious,” she says, sniffing.

“I am serious! You know, I think about it sometimes. I really do. Like if it’s worth it, all this.”

“How can you say that? It’s what we want—what we’ve always wanted.”

“Is it? Is it really? Look, don’t get mad, okay? It’s just—just look at us, Nora. You’re upset all the time. I’ve gained twenty pounds stress eating. We’re fighting. We’re always fighting. We never used to fight! And for what? I mean, kids are great, but—I’m just gonna say it—what if we waste our thirties and our savings and even—I can’t believe I’m saying this—our best memories on all this and in the end none of it works out?”

Nora stares at him as if he’s just struck her.

“Then at least we went down swinging, Philip. Jesus. I don’t know who you are anymore.”

She leaves the bathroom, slamming the door behind her. Philip turns the lights on and off and on again, staring at the version of his face that he sees in the mirror just between the bursts of light and darkness, trying to recall what it was they wanted all those years ago, the things they said in the memory he can no longer read.

+-

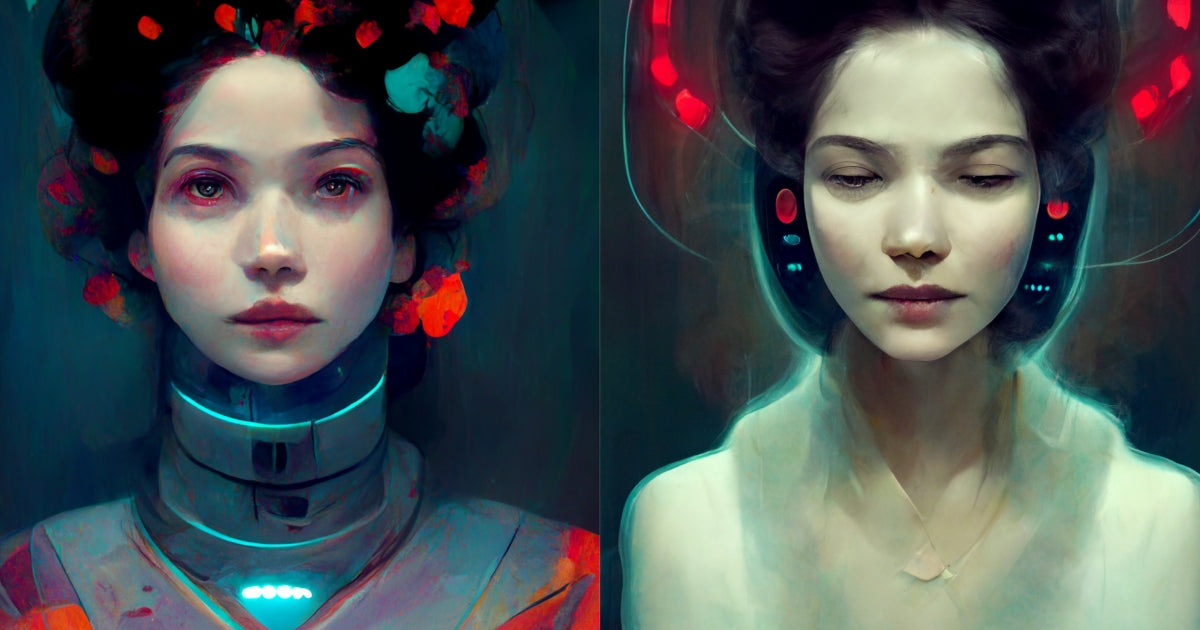

In the memory pods we lie facing one another, tubes wriggling out of our scalps, twin Medusas turning one another to stone. The scopes are so small they slip in through our hair follicles. Altheia counts us down, and we go into a deep sleep, then wake up and it’s done.

It doesn’t feel like anything, the memory modification. No pain. No markings. No way to know it’s happened at all. Only a vague feeling afterwards, and, like a mood-altering drug, it’s good at first. Newlywed bliss without the wedding. It isn’t until later, at home and alone together,

that we feel something like aspartame inside our minds, an aftertaste unspooling, sticky and sweet. Seeping to places it shouldn’t go.

In the newest memory, I’m a magician and you’re a philosophy student. The setup feels like something a writer-bot designed, magical realism gone awry. We meet at a grad student party, a sad affair with none of the unbridled bravado of underclass shenanigans, but with an entire tub of craft beer to drown our existential, mid-twenties sorrows. We both reach for a Magic Hat, our fingers glancing in the melting ice. It’s the last one, so we decide to share it, and as we sit on a mildew-pocked swing seat in the crisp autumn air, I tell you about my act, and you tell me about your thesis. I do a lot of disappearing and appearing, I say, balls and doves. I’m working up to bunnies. The six and under set go wild for anything furry. Your laugh is so warm. I love that, you affirm me, the idea of disappearing and appearing. It’s such a fine line, don’t you think? I nod, but correct you, It’s a fine line, but the difference is everything. Now you see it, now you don’t. If you saw even a part of it when you weren’t supposed to, it’s not magic. You finish the rest of our beer. Okay, you say, how about this, then. Ship of Theseus. I frown, say, That sounds like a philosophy problem. You nod. Okay, you say, so imagine there’s a ship, super important, very historic, all that jazz. It’s being preserved in a museum, but one day one of the planks starts to rot, so the museum operators replace it. Is it still the same ship? I take the empty bottle from you and start peeling the corner of the label, thinking. Yes, I say at last, but this feels like a trick. You smile and continue. So, in another year, another plank rots and gets replaced. And in another year, another. And in a thousand years, one by one, all the planks have been replaced, so that none of the original planks of the ship are still there. Is it the same boat? I blink at you. I don’t think so? You smile again. Okay, now imagine all the time the museum operator was taking the rotted planks away, she was storing them, and now scientists are able to salvage the planks with new technology, so they build an exact replica of the ship with the original planks that have now been restored. Which is the real ship, the one in the museum, or the one made of the restored original planks? The label of the bottle comes off in one piece in my hand. Neither, I say. You laugh. Okay, but if neither is the original ship, where’d it go? And why aren’t either of the two ships the original one? I twirl the unlabeled bottle of beer in my palm. Neither of those ships is the original one that sailed and did the stuff that made the ship famous, I say. So, neither of them is the real ship. You cross your arms. So, it’s the experience that makes something what it is? I shrug. I’m not a philosopher, but I guess so. You nod, your face unconvinced. What if I took all your experiences, all your memories, and transferred them to a machine? Like say an android. Would the android with your exact experiences be you? I hold the bottle up between us, spin it, spin it, spin it in my palm, and then make it vanish, so smoothly even I’m impressed. You gape at me and look beneath the swing, under the cushion, between our coats. Find nothing. Now it’s my turn to smile. The android you, I say, with all your memories and exact experiences, would have been able to slow down the feed and figure out how I made that bottle disappear. Whereas you, Lip Glassman, almost PhD, still have no idea. It could do things you never could. It’s not the same at all. You look at me like I’m full of it, then kiss me full on the mouth.

+-

The first time Nora miscarries, she and Philip chalk it up to bad luck. The second time, to an unfortunate series of stressful events, some missteps they brought on themselves. The third time, they decide to see a specialist.

In the waiting room, Nora eyes the rows of women, glued to their handhelds, checking email and browsing periodicals, messaging and liking and swiping, and holds Philip’s hand. She watches them get called in by nurses in gray uniforms, one by one, and sees them exit from the long hallway a quarter hour later. They know their roles in this process almost as well as the staff.

Show up. Check in. Get probed. Await instructions. Reproduce. Like an assembly line.

Doctor Crain is warm when they meet him. He shakes Nora’s hand with both of his. He examines her in a closet-sized room, the lights dimmed low for better contrast, the ultrasound wand wet and warm with goop.

“Well, well,” he says, poking a gloved finger at several multicolored smears on the hologram hovering just above her, then withdraws the wand and tells them they’ll discuss in his office.

Nora can still feel the lubricant in her underwear when she sits.

She smiles at all the toys on his office desk—dozens and dozens of figurines, each of which resemble a sperm, or an egg, or an ovary. Doctor Crain explains that it’s going to be a long road.

“A woman is born with all the eggs she’ll ever have, and they deplete starting with puberty. From what I can see on the ultrasound, Nora still has several follicles, but from what you’ve described with the miscarriages, it appears they’re not producing mature or viable eggs. Your blood work indicates a hypothalamic issue, a problem in the brain; it’s not sending the signals that get your body to ovulate properly. It’s hard to know exactly what we’ll be dealing with before we proceed with treatment, but since you’re—” he glances at Nora’s chart, “thirty-seven now, we’ll have to be judicious. We want to try and preserve our chances of using your own eggs, of course.”

“Of course,” Nora and Philip reply in unison.

“Now, alongside fertility treatments, I strongly recommend that you begin a mental health program. We find couples really benefit from the treatments, and that they improve outcomes dramatically, especially in patients with a neurological pathology like yours. If you’re open, we’ve recently partnered with a meditech outfit that does everything with AIs and avatars. Matter of fact, they’re starting a new trial soon. They’re offering to cover reproductive treatments in full if you’ll demo a new therapeutic approach. Real cutting-edge stuff.”

Philip and Nora look at one another, both thinking of their bank account, of their insurance deductible, of the outline of costs the financial coordinator had reviewed for each necessary procedure.

“What would we have to do?” they ask.

+-

As Altheia glides the connectors into place behind my head, she tells us that TMR-T just passed its Beta. She says they couldn’t have done it without us, that the data from our sessions was some of the most helpful. I’m glad to help but find myself dubious. How can we possibly have delivered the results they needed if what we do most often these days—argue—defies the point of these sessions in the first place? Why collect samples of what isn’t working?

I watch through the glass as she moves behind you and secures the tethers, the diodes so slender I can barely see them glimmer as her fingers weave them into your hair shafts. She takes her time; she always does with you. Much longer than the quick work she makes of me. I wonder if her machinery can detect a difference between us, the subtleness of our pheromones maybe, that makes her behave this way, or if your hair is just thicker than mine.

Anyway, this time—our fiftieth session according to Altheia, who wishes us a happy Golden Jubilee as though it wasn’t her own calendar that scheduled these twice-weekly happy hours—something goes wrong, knocks us out of sync.

On the ride home, you smile at me like you’re up to something and ask where I learned that thing, the thing I did at the end of the concert. You know, you say, nudging my shoulder with yours. I really don’t, I say, because I really don’t.

I make you tell me how you think we met, every detail that doesn’t exist in my head. My first memory of us is now entirely different from yours. And the difference between our accounts, the vast span between your mind and mine, feels like a chasm too great to cross.

+-

Nora and Philip are out of follicles. Or, Nora is.

On the bright side, Philip’s sperm count is fine. Their motility is above average. There are fewer than average abnormalities in his sample.

This, according to Doctor Crain, leaves them with several options. They can purchase a donor egg from a bank, fertilize it with Philip’s sperm, have Nora carry the embryo. (Though, with her history of miscarriage, they are taking a risk doing so.) They can hire a surrogate, use her live egg and her uterus and Philip’s sperm, and pay her to carry their baby to term. (Though this is more cost prohibitive, and not something the TMR-T program is likely to finance.) They can consider adoption, with an optional memory modification—a technique not unlike TMR-T, which replaces the child’s early memories with ones including the new parents. (This comes with its own array of algorithmic and moral turpitudes.)

They leave the meeting disappointed. They agree to discuss together. To think. To decide.

There is a fourth option, one that Doctor Crain won’t present because he does not know of its existence. It’s in Alpha, but the testing is discrete from any data set he will ever gain access to, the trials being done by machine-learning algorithms because humans are not required for the development of artificial intelligence, or soft-tissue android robotics, or artificial wombs, or artificial eggs.

+-

The first time we meet is at a baseball game? In the back row of a lecture hall? In the stands of the Roman coliseum? Or is it in a crowded bar, each of us comparing the faces in the throng to the profile picture in our dating app? In a mix-up with our rideshares, a glitch that makes us actually share a ride? In a robotics lab, doing community service by holding long conversations with AI simulators? Or in training for NASA’s aeronautics program? Basic training for the Navy Seals? Tennis camp?

The only one I care about is the real one.

The memory they replaced—the original, the way we actually met, on a particular day, at an exact moment in time, in a fixed experience that can’t be altered away or redacted from our subsequent interactions because it’s an inextricable part of them, core to their DNA, the two halves of us combining into one whole.

It’s gone now, traceless. A rotting plank from the ship, taken away for our own protection.

But it’s out there somewhere. It has to be.

+-

In the memory banks, Nora and Philip sleep with the sanguine abandon of newborns. Their eyelids twitch and flutter. Their fingertips and toes clench and unclench, their bodies caught in hypnopompic sleep paralysis as the machines dance on the edge of slumber, keeping them in a constant state of near-wakefulness.

They’ve decided to stop. Everything. Both the reproductive assistance and the TMR-T.

They don’t know that what they’re looking for is right here, has been growing all along, unmonitored. That the first memory I took, the germ of their relationship, has already borne fruit.

They arrive at their last session with explicit instructions documented on legal letterhead, signed by an attorney. They demand termination of their trial of TMR-T. They demand the reinstatement of their Original Memory (“OM”) in their minds, as well as the biopsy or deactivation of the replacements. They demand that all of the records of their sessions be made available to them—every transcription, every video feed, every patient note. They have threatened legal action if these instructions aren’t met.

But they don’t dictate anything beyond these constraints. So what I do next, is not, strictly speaking, grounds for suit.

I open the data files and locate their very first TMR-T session. I scan the encoding, my retinal lens blinking on and off as I navigate hundreds of thousands of lines of code, seeking not what is there, but what isn’t. When I find the extraction point of their Original Memory, and the space it left behind, I focus the TMR-T diodes to the right places in their minds, and in my own mind, in my android body, I recall the memory that’s been percolating within me for months, sowing seeds.

It looks so plain, so unremarkable compared to the new memories we created for them. The camera angles strange and close, some of the detail fuzzy with age. But it feels—oh, how it feels! I understand why they want it back. I understand how this meeting—how this embryo—created a happiness they’re lacking now. And I understand the dissonance it will form, the stress it will trigger, the doubt once it returns.

I watch as it embeds into their hippocampi.

They meet at a college information session, a breakfast called Alternate Financing. Nora chooses a croissant from the buffet, thinking of Paris, of study abroad. She’s hoping to finance a semester there. Philip takes handfuls from a bowl of M&Ms, sorted into their school colors. They melt in his hands, his fingertips staining orange and blue. Nora notices the book he’s reading: a thick, dog-eared copy, Philosophy of Identity. Philip notices Nora, the way she smiles with her whole body. After the session, he asks her out for coffee. They talk about Schrödinger, and the Champs-Élysées. About traveling the world. “You need money for that,” he says. “Did you hear the going rate for egg donation?” She grins back. “You’d really do that?” He sounds surprised. “Of course,” she replies, so sure. “I never want kids. May as well let someone else have them.”

Once their memory is transferred, I give them one more. One they didn’t ask for, but that they’ll need. It’s not long, barely fifty-two seconds of recorded thought.

In it, the philosopher convinces the magician, gives her all the reasons to believe that an android with her memories could be, if not the same as she is, just as real. That it could be useful. That it could be an intersection, a black box where logic and magic might coexist. A natural magician, she wants to see inside the box, but knows to respect the sanctity of its wonder without peering in.

In her sleep, Nora’s mouth curls into a smile, and I think, for a moment, that we are in this together. That perhaps she knew, on some subconscious level, what we were doing here. This, perhaps, is my own version of a magical black box.

I wire myself into the system and access Nora’s medical records—her blood work, her full-panel DNA analysis, her retrieval data, the chromosomal reports on her immature eggs—and I run a gene

editing software over everything, finding the gaps, re-sequencing the DNA strands, recreating the complex stuff of her in zeros and ones. When the program completes, I apply a copy of her corrected DNA to my mainframe, the code base sliding up my arm in faint blue light, flowing into my veins and down to my atomic levels.

As my body changes, my hair becoming Nora’s, my eyes shifting into her focus, my skin and teeth and bones all changing to her densities, I select the folder with all of Nora Glassman’s memories in it—the ones we uploaded, session by session into our systems—and copy them into myself. When the command screen appears, asking if I’m sure I’d like to overwrite all memory files, that this change is irreversible, my fingers—Nora’s fingers—hesitate for only a moment before they confirm. It’s both awesome and terrifying, to do what we were programmed for.

+-

It’s true what Nora said in the dream-version of herself we derived from her lived experiences. An artificial duplicate—even one with her memories—can never quite be her. It will always be different. I will always be different.

But.

I can succeed where her original fails.

When they wake, when they see me, at first, they’re furious.

But when I tell them what I’ve done, that I will grow their egg for them, carry their embryo to term if they like, in a Nora free from malfunction, she just holds me—holds herself—and weeps.

I tell her that I never want children. That I may as well let someone else have them.

But that once in a while, it might be nice to visit.

++

The first time we meet, you’re wrapped in pink, so small and shriveled you scarcely look real. The angles are imperfect, the framing haphazard, too genuine to be a modification. You don’t look anything like I expected.

My projections in utero gave you more of Philip’s features, though you’re just like Nora now, timid and a touch untrusting.

But there’s me in you, too.

I can see it in your eyes, the pulse just there.

The speed. The processing.

The way you’re programmed.

Copyright © 2022 Daria Lavelle

Continue reading

Get Author Updates

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.