Potato

By Ken Altabef

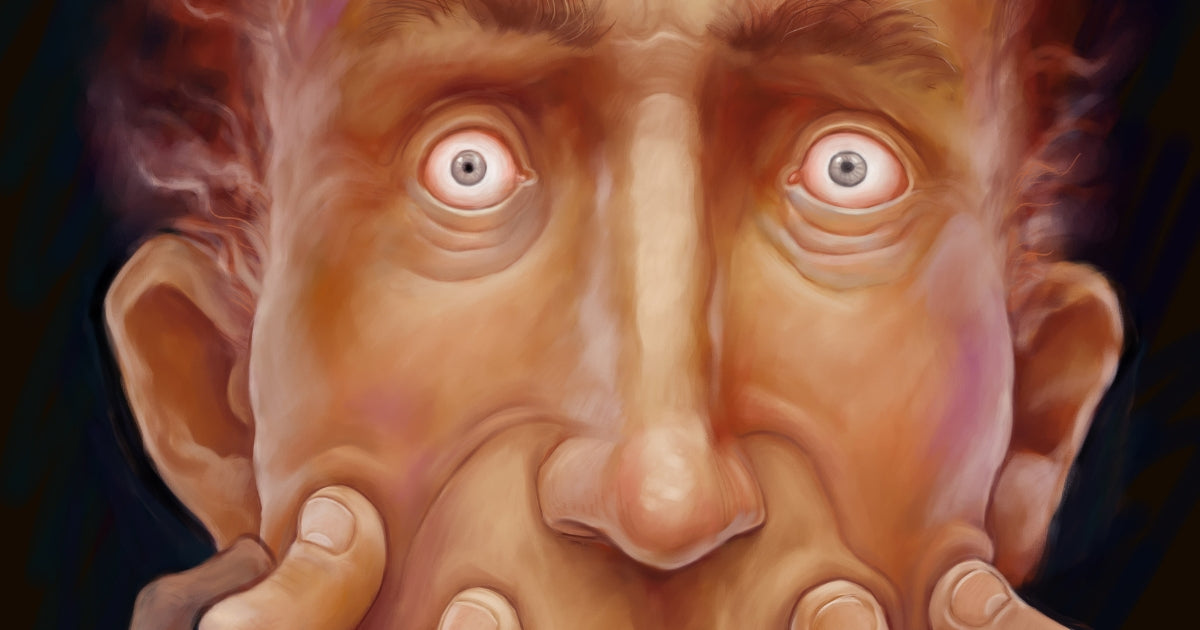

The water in the bathtub went cold six days ago, could even be a week. There’s no more hot water, the pipes all clogged. The bathwater is so green with gunk I can’t even see what’s underneath, but I don’t want to see. Lord, it all itches something fierce, especially down in the crotch where it’s snaked between my legs. I want desperate to pull it out, but I’m afraid. When I tried to pull out the shoots I found in my ears yesterday, it hurt like hell.

The damn stink is the worst. Raw potato doesn’t have itself a strong smell but when you’re surrounded by it, growing fresh and thick on the walls, covering the whole room—the ceiling even—it’s enough to make a body want to vomit. I feel a tickle down my throat as it shifts, a playful little tug at something or other inside me, trying to make me gag. But nothing comes up, the pipes clogged there too.

I should’a run away when it all first started. I should’a run like hell when I found that first one. There’s a spot on the mirror where it hasn’t grown all the way over yet, and I catch sight of myself—what a horror I look! My skin is all milky pale and as wrinkled as a prune, but they won’t let me get out of the water. I see myself, like a withered old scarecrow lying in a coffin full of green water, and I remember.

Potatoes are supposed to have eyes, but when this one opened, I near fell down sideways. I’ve been digging potatoes for thirty years in that little vegetable patch out back of my house, but I never had one look back at me, and with such a sad, soulful glance as that. Its one eye was brown, as you might expect, but pink around the edges where it should’ve been white. It glistened wetly. And then it winked.

Nowadays, people see faces on damn near everything—a man in the moon, Mother Teresa on a biscuit, Elvis almost everywhere, and the Lord Jesus on a cheese sandwich. But it still nearly bowled me over. At first. At first.

But after I held that little ‘tater in my hand for a while, and it was warm and kind of soft at that, it didn’t seem quite so strange. Unusual, certain. But not too strange at all. It hummed at me, that sweet little thing did. A slow, sad tune like something I might’ve heard a lifetime ago when I was a young girl, a melancholy lullaby meant to send troubled children off to sleep. Up and down, the tune went, but never so much up as down, lower, lower, slower, slower. It seemed the most natural thing in the world.

But what should I do with it? I figured the poor little thing could do with some water, so I filled up the old mop bucket, and I knew ‘taters like it kind of dark, so I put it under the bench out in the garage. But after standing there a while, and thinking and listening, I thought that crusty old bucket wasn’t so good and my lonely garage not near good enough, so I brought it in the house and let it soak in my wedding bowl. That was Stratford crystal there, fifty-years-old. But it still needed dark, so I put it under the bed and pulled all the window shades nice and tight.

I lay down, dead tired, but I didn’t want to sleep. I wanted to run like hell—to run and run and run. But that little humming song told me I was too tired to move and put me straight off to sleep. I didn’t even dream, not as far as I can reckon.

Next day, I went over to market and bought fresh eggs and some sliced turkey and a couple normal potatoes, and I almost told that Jennie Flaherty about that odd little ‘tater of mine. I wanted to tell her, I did, but the words just wouldn’t come. It was all just about the weather and the local gossip and such. No news about a humming potato. Certainly not.

When I took that bowl out again, I saw the ’tater had sprouted! It had little shoots coming out the sides—yes indeedy—four crooked little shoots with tiny little fingers and toes. The eye looked at me, still so sad and lost like a little pup. And the potato hummed. It sang me that low, sad song as the days went by and by.

After about a week, my little tater-child was fast outgrowing that bowl. It had got itself full-grown arms and legs, and a second brown eye (though it was a bit smaller than the other), and a curl to its shape looked just like a baby. I emptied it into the bathtub, filled it up with warm water and put in some fertilizer grow-stuff I got down at the store. That stuff turned the water kind of green so I couldn’t hardly see my sweet little baby no more, but I could still hear it hum to me. I didn’t go out of the house much after that; I knew I shouldn’t leave a child there in the bath alone. No mother would.

And the song, that song was just for me. It didn’t want no one else to hear.

When my boy Harlan came round for his monthly visit, I wouldn’t let him go into the bathroom. I couldn’t think of a good reason, neither. If I told him the pipes was broke, he’d want to get at them with a wrench. He was handy like that, always fixing things. So, I started yelling at him, and I cussed at him some and finally pushed him out the door and gone. “Crazy ol’ bat!” he said, and it wasn’t the first time.

I wanted to chase after him, I wanted to scream out to him, but I didn’t. My baby needed me. A momma can’t just run off like that.

It grew fast after that, filling up the tub, eating up all that fertilizer stuff, I guess. Its legs went so long they dangled over the sides. It looked a frightful sight. It had peculiar skin, all dry and brown and crinkly no matter the water, just like a regular potato does. Its head looked like a big old potato with those sad bloodshot eyes, and it had a lump of a nose, and a mouth with crusted, weeping lips. No hair, but the dome of its head shifted here and there like something was moving underneath, just below that crinkly skin. No one could possibly say my young man was handsome, I know, but nobody ever said my husband Jack was too easy on the eyes, neither.

It made a different song than just the humming, now it had a mouth and all, a song made up of no real words anybody could understand, except I did understand them. It said it loved me and it wouldn’t ever hurt me. It wanted to go outside, it wanted to go visiting other people and do some real living. I guess just about anyone can understand that. I guess. I didn’t think much of that kind of talk, though. Not for him. I could dress him up in some of my husband’s old clothes but that just wouldn’t work. He couldn’t go anywhere looking like the way he did, with that nasty potato skin all over. And he smelled like fried eggs, cooked too long on a greasy skittle. Though now I come to think of it, I must admit my Jack might have smelled a fair bit worse.

The water was surprisingly warm when I climbed into the tub with my young man. I felt so many different things—the nourishing embrace of moist earth, cool clear water, tangy loam. His long, boneless fingers caressed me as I clung to his rough, papery skin. He was gentle with me, and that helped—and it sure did hurt that first time. First time in a long time. He whispered constantly all the while, and that helped. I can’t rightly recollect what he said, but I’m sure they were nice, tender things.

Next few days, my potato spent most of its time in the garden, digging up some more of them strange things and putting them in the sink, the bathtub, and damn near everything else that would hold water and fertilizer. Soon the whole house stank, and the walls started to crawl. My potato man had become way too busy to pay me much mind. I thought about my boy Harlan and wished he’d come down for his visit, and then I remembered the way I’d run him off and all. Then again, he never sang me such a pretty song.

When it left me, I felt hurt and afraid. I shouldn’t have to stay in this dirty water all the time, and like I said, the way it’s crawled up inside me’s no good neither. My belly’s all swole, and I feel it moving. It hurts, and I’m afraid. A mother shouldn’t be left alone, surely not when she’s expecting. But I’m not alone, not really. A body could go near deaf from all the humming and singing round here. Now the whole house sings.

I was surprised, that’s all. I thought he couldn’t go nowhere with that ugly potato skin of his. But then I noticed the potato peeler and all those rinds on the bathroom floor.

No worries, then. I think he’ll pass just fine.

Copyright © 2021 Ken Altabef

The Author

Ken Altabef

Continue reading

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products, and sales. Directly to your inbox.